| "I am in the unthinkable situation most people can't bear to contemplate." |

Wave is a grief memoir, a genre exemplified by Joan Didion, Isabel Allende, and CS Lewis. I dunno—I think Sonali Deraniyagala might trump them all. Not that this is a competition anyone wants to win. She lost her entire family (two sons, a husband, and both parents) in 2004's horrific tsunami. Hundreds of thousands of people died that day, but here, we are focusing on this family, this particular loss. It is a stunning book.

The story crashes in on you immediately, locating you with the family the morning of the devastation, just as the sea was coming in but before anyone realized what was wrong. I read this first chapter in one gasping go, my heart pounding, unable to look away or think about anything else till it was done. You don't really want to diminish such an experience by calling it a "hook," but by god, I was hooked. From there, the pace slows a bit as the author walks you through the aftermath, but it never really lets up. Strangely, I didn't want to put it down for a second.

I was struck by the "army of friends and family" who kept Sonali from killing herself that first year. In the US, our ties to our nuclear family are often strong, but our ties to our extended family and community can be remarkably weak, relative to other cultures. I don't think I have "an army" of people who could watch over me 24/7 for months on end. In my culture, if I were in that position, I'd be committed to an institution. That's what we do. In George Packer's The Unwinding, which I reviewed here last month, I noticed how alone Americans are, relatively speaking; the only person who could rely on extended family to help her out during financial crisis was an Indian immigrant.

I would say "I can't imagine what it must be like to lose your entire family," but that's what this book does. Makes you imagine it. I also have a husband, two kids, and two parents, without any of whom I'd be unmoored, but ... the kids! To lose your babies in an instant like that. Grief isn't something you can recount easily, it doesn't fit in the frame. It's like those blue whales she observes from the boat ... too big to fathom. You can only get bits at a time. If ever you needed a reminder to be grateful for what you've got, for every mundane second of what you've got, Sonali will remind you.

There's a little gift buried in this memoir that doesn't get mentioned in reviews: the glimpse at a life that is both so similar to and so very different from my own. Sonali is Sri Lankan, upper middle class, and married an Englishman. She raised her family biculturally, across continents. That alone was interesting to me. The physical descriptions of Sri Lanka—the sea, the jungle, routine hoards of cranky elephants—were colorful and fascinating. I felt like I was getting a cultural education right along with the Job-like horror story. It almost seems in poor taste to mention it, like you're not supposed to notice how interesting her family is. Or was.

| Steve, Vik, and Malli |

And that's part of what makes this book work: you get caught up in how interesting they are. Malli in his tutu, Vik's fascination with eagles, Steve cooking dinner. She fleshes them out slowly; you get to know them after they are firmly established as dead, and it becomes ever-more difficult to believe they could possible BE dead. How could such real people be dead? They had futures, each of them, and you find yourself rooting for them impossibly, hoping somehow it'll all turn out all right in the end.

I was struck by the "army of friends and family" who kept Sonali from killing herself that first year. In the US, our ties to our nuclear family are often strong, but our ties to our extended family and community can be remarkably weak, relative to other cultures. I don't think I have "an army" of people who could watch over me 24/7 for months on end. In my culture, if I were in that position, I'd be committed to an institution. That's what we do. In George Packer's The Unwinding, which I reviewed here last month, I noticed how alone Americans are, relatively speaking; the only person who could rely on extended family to help her out during financial crisis was an Indian immigrant.

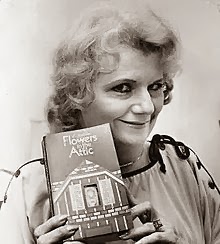

| Sonali Deraniyagala |

Some reviewers have complained that the book is too sad to be borne. I didn't feel that way: I struggled much more with Leaving the Sea, a book of short stories I finished right before I started this one. I don't know how that fiction could be bleaker than this reality, but there is an intimation right from the start that Sonali is going to be OK somehow. Maybe simply because she is there, writing this memoir—she couldn't do that if she wasn't a little bit OK. Some people survive but never do come back to life after tragedies; they remain shells for the rest of their days. This writer (and how is she not a professional writer? Her writing is amazing) seems like she has a shot at being all right. That resilience is what makes the book bearable.

Note: Much of this review is shared from my review over at Goodreads. Feel free to join me there.