After a lifelong affair with storytelling, becoming a professional

storyteller was one of the highlights of my librarian career. At the time, I

naively thought that being good at my craft (as I was told I was) meant I could

put my stories on paper and instantly become a novelist. Think again! There is a huge

difference between writing and storytelling. As the cliché goes, writers are made,

storytellers are born. But like Yours Truly, you may be a fantastic tale-spinner

and yet lack all the skills that makes a good novelist.

Family lore

asserts that I was involved in storytelling way before I learn how to read. I

used to memorize fairytales and then create my own version which I would retell

to family, servants, pets and whatever captive audience I could get hold off.

It was a form of oral fanfiction. As I grew old, my storytelling experiences went

underground, until I found myself in Library School.

There I

learned that storytelling was a crucial skill for good Children’s Librarians. There I heard about the great Augusta Braxton

Baker and other pioneer storytellers/librarians. I also got to meet and watch

real storytellers performing their magic. One of the landmarks of those wonderful years

was a chance to do library programs in which I polished my old art and went

through marvelous experiences that plied me with anecdotes to dine on for

decades.

|

| Augusta Braxton Baker |

Technique vs. Drama

Encouraged

by my storytelling success, I decided that I had the skills to become a true

novelist. This crass mistake derived from my confusion between the terms “storytelling”

and “story writing.” The first is all about voice, words, atmosphere, vigorous

action, drama and wonder. The second is all about method, prose, rules and

in-depth characterization.

Popular

commercial writers like to think of themselves as “storytellers,” consequently they

rely more on dynamic action and dramatic mood than on literary technique. Their

lack of fine writing skills is what their foes will bring up when attacking

their work. On the other hand, think of Henry James’s novels, very little happens

in them, but you can’t deny his masterful prose or his powerful characters.

The

majority of fairy tales were originally found within storytellers repertoires.

But when early folklorists shuffled those narratives from the oral realm to a written

page, the tales underwent drastic modifications. Early versions of well known tales

contained disturbing elements such as Sleeping Beauty being raped by the prince

or Rapunzel having twins out of wedlock (something they forgot in the

Disneysque version called “Tangled”.) Language had to be cleaned up and the

whole text had to undergo a refining process. Each story found that

transcription to paper meant to be bound by literary technique and conventions.

|

| No twins for this Rapunzel! |

Rules vs. Spontaneity

Storytelling

is linked to an old traditional activity known as oral narrative. It goes back

to cavemen telling tales around the camp fire. Most cultures will have some form

of traditional storyteller, from the Irish “seancaid” to the Jewish “maggid.”

In the past, storytellers have been seen as shamans, healers, keepers of

tradition, even as intermediaries between the sacred and the profane. Such is

the strength that comes from spinning a tale.

Telling a

story, even to an adult audience, is a dynamic-spontaneous activity. You can’t

go back to polish a draft or edit mistakes. What comes from your mouth is what

your audience gets. It’s like acting in a play, if you goof you get booed. If

you forget your character name, or skip a major moment, your audience will know

and will let you know. And worse than being pelted with tomatoes, like actors

of old did, is to lose your listeners’ attention. It is the equivalent of losing

their respect.

You have to

prepare in advance for predictable disasters. So you said “Princess Alice”

instead of “Princess Alexandra”? Then you quickly explain that Alice is

Alexandra’s evil twin who, in fact, is working wit Dark Forces to take over her

sister’s throne. I know it sounds far-fetched, but believe me, it does work.

I have tried it. Did I say the storyteller is an actor? A stand up comedian might

be a better description.

Is your audience yawning and staring at the clock? Wake them up with some

unexpected plot twist. In Romana, the

Jewish-Italian version of Snow White,

the heroine does not find shelter with benevolent dwarves; she ends up at the

lair of seven ruthless thieves! I often imagine this twist must have come about

as a desperate storyteller attempted to get his audience’s attention back with

a “Hey, guess what? Romana has just been caught by the most dangerous gang in the

entire Italian peninsula. Yes, seven hardened criminals, and there she is, hanging

from a tree branch, wondering if she should climb down and take her chances with

these strapping lusty outlaws.”

|

| Darth Vader and Son |

You may

think this only works in front of a live audience, but surprise twists are

useful in all forms of storytelling, especially in book or film series that

have dragged too long and are reaching the point where the reader’s patience is

wearing thin. Who would have imagined that Darth Vader would turn out to be

Luke Skywalker’s father? It was the most unforeseen moment of the Star War Saga

and left us waiting breathlessly for “The Return of the Jedi.” Stephanie Meyer was aware that half her

fandom wouldn’t be happier with Bella choosing to be Vampire Bride instead of

the Wolf Man’s Wife. Her solution was to turn Jacob into Bella’s future

son-in-law and leave her readers pondering about the possible incoming “Reneesme’s

Adventures in Lycanthropy.”

Followers of

George R.R. Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire

were a bit confused after Clash of Kings,

the second book of the series. Not only was it more slow-paced than the

previous Game of Thrones, but Martin’s surprising killing of the apparent

protagonist had left his devotees treading on thin ice. The only thing they

were certain was that the one great villain of the story was Ser Jaime

Lannister. How else could one describe a man who had backstabbed his king,

impregnated his much-married Queen (who also was his twin sister), ambushed

good Ned Stark in the street, and threw children off ramparts?

Well, in Storm of Swords, the third book in the

saga, Martin did the unthinkable: he presented Jaime as a victim. By turning

him into a POV character, the author granted him a chance to tell his side of

past events, baffling those who thought him a monster. That changed the

viewer’s perception of the character forever, transformed the Kingslayer into a

sort of heroic figure, and made Storm of

Swords the most read, discussed and loved book of the entire saga.

|

| Ser Jaime Lannister from Kingslayer to tragic hero |

Archetypes

vs. Well-Developed Characters

But

storytelling is not totally devoid of pitfalls, one of them is lack of time and

space to develop multifaceted characters. Thus, storytelling has to rely on

archetypes: The Charming Prince, Cinderella, talking animals, and others that

just by mentioning their name have the spectators imagining looks and

personalities. When telling a tale in front of a live audience you don’t have the

time to give a complete biography or a full physical description therefore you

to have to simplify. One of my tales started like this, “Miguelito was a very

poor mouse. So poor was he that his pants lacked pockets because he lacked

loose change.” Obviously, if I was writing the tale I would submit to the “show

not tell” clause, and never mention the word “poor.” In storytelling you just

have to.

When Isabel

Allende published The House of the

Spirits, critics pounced on her accusing my countrywoman of creating a bad

copy of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred

Years of Solitude. Indeed, her book owed plenty to Garcia Marquez’s masterpiece, but Allende imbued enough political ideology and her own family

lore into the novel to establish a distance. Moreover, she had one advantage

over the Colombian author, she had well-developed characters.

This may

sound like anathema. Don Gabo is a literary giant, nobody surpasses him in

telling stories, describing imaginary worlds, and creating a family tree

spotted with intrigue and domestic drama, but his larger-than-life characters

are iconic images, never flesh and blood personages. Look at his fictional

women. We know that his many Renatas, Remedios and Amarantas fall in and out of

love, get pregnant by the wrong man and die in childbirth, but do we know what

they think? What they like to do in

their spare time?

Garcia Marquez is a terrific storyteller and

as such he relies on characters that are a combination of mythical figures and

anecdotes. He could stand in front of a crowded theater and verbally convey his

novel because it belongs to an oral storytelling tradition. Unlike him, Isabel

Allende’s characters are too complex and experience too much interior drama to

be put into five words. There is no way to explain briefly about mystical

Clara, forced by fate to marry a man that belonged to her dead sister. And how

would you verbally express the horror, pain, and humiliation of Alba as she goes

through physical torture?

|

| Meryl Streep as Clara in "The House of the Spirits" |

If I had to

take one book with me to a desert island, I would pick The Holy Bible. Aside

from its spiritual content, it’s the best storytelling I have ever laid eyes

upon. Within its covers you find everything: political trickery, supernatural

events, domestic squabbles, war epics, romance and lust. We love biblical stories

and their protagonists have become household names, but do we see them as

real-life characters? Do we get to know their point of view? We know King David

liked women and played the harp, but what was his favorite food? We

know Sarah hated her husband’s concubine Hagar, but do we know if Hagar hated

her back? Do we know if Hagar was happy with Abraham?

Every

March, Orthodox Jews are subject to one great story hour. The reading of Megillat Esther (The Book of Esther) is the highlight of the Purim Holiday. The

synagogue becomes a big storytelling room. All gather to hear the rag-to-riches

story of Esther, a nice Jewish girl who is taken away from her home, and after

winning a harem beauty contest, becomes Queen of Persia. I love to hear how even

after marrying the most powerful man in the land, Esther is still subject to

palace intrigues, has to hide her Jewish identity, and strives to save her

people from evil Haman.

The story

ends in a colossal triumph after Esther manages to save Persia, the Jews and

herself through cunning and courage. It’s Cinderella meets Joan of Arc, but do

we know Esther? Do we know how she felt about her king-husband? Is she home-sick? Where did she learn to play

bedroom politics and how she went about it? Knowing the answer to all those

questions would make The Book of Esther

a terrific novel, but it would probably take two days to read it in the temple.

Even the most pious audience would be snoring before the reading was over.

Continuity vs. "The End" word

Whenever we

think of the term “storyteller,” the name “Sherezade” comes to mind. Wrapped in

her veils, the protagonist-narrator of the Arabian Nights is the teller of

stories par excellence. She alone

performed the prowess of spending a hundred-thousand-and one nights weaving

stories to charm a king out of his psychotic misogyny. What is so compelling about

her feat is the impression that Sherezade spends every hour of her existence at

her craft, that her entire life is linked to the continuous act of

fable-spinning. It’s only by the end of the book, after it’s disclosed that she has delivered two sons for the Sultan,

that we realize that a lot more went on in

that bedchamber than just telling tales.

|

| María Montez as Sherezade |

Sherezade exemplifies

one of the greatest joys of storytelling, its continuity. Unlike novel writing

that is bound to arrive to the word “The End,” a tale could go on forever. A

storyteller could call it a day just to retake the narrative thread the following

day, or night like Sherezade did. A novelist can give up on his craft, never

write another book, a great novel may never have a sequel, but storytelling is endless.

You have cycles of tales connected to one single protagonist like Anansi, the

Spider or Stupid Jack. That is what written series and storytelling have in common,

the infinite possibilities.

Agnes

Newton Keith was an American bestselling writer that wound up experiencing

stranger than fiction events. In 1942, she and her small son were taken into

captivity by the Japanese. For the next three years, she lived in a civilian prisoner

camp, away from her husband and enduring privations, malnutrition, slave work,

plus physical torture and a rape attempt. Throughout her captivity, her utmost

preoccupation was the survival and well-being of George, her little boy. One

way she found to keep up George’s morale was an evening storytelling session

that centered on the exploits of a super hero known as Big Game Hunter “Keith

of Borneo” (later joined by “Jack, the Giant-Killer”.)

|

| Birthday card , Agnes Newton Keith sent to her husband while still in captivity |

One night

she realized that other children in her compound had gathered around her

mosquito net to hear her story. At first, Mrs. Keith wanted to yell that this

was only for George, but finally she gave in. Her daily story session became a

source of pleasure and comfort for the youngsters in captivity and a way to

maintain her narrative skills. She stretched Keith’s adventures as far as

credibility could allow, sent him on trips around the world, personalized the

stories and in every way proved the power of storytelling and the capacity for

a tale to continue ad infinitum.

The Interactive Storyteller vs. The Writer in

the Ivory Tower

Mrs.

Keith’s anecdote illustrates another advantage that storytelling has over story

writing: you get to know your audience. When we write our first bit of fiction,

we write it mostly for ourselves. We are the target audience and we grow

attached to that piece because we like it. Then we expose it to the criticism

of family and friends. We start modifying

our text to suit the audience’s needs, a process that expands as we move from

acquaintances to agents and publishers. We are always running into new more

demanding readers, while in the horizon looms the threat of the “real public,” a

terrifying but foreign group.

In

storytelling you have no such problems. Even if you may be awed at the

prospect of meeting listeners for the first time, you’d have plenty of data on them.

You will know their sexes, occupations and ages. Novelists have three abstract

age groups to choose their target audience from: children, young adult or

adults. In storytelling, age groups tend to be more specific.

My first

story session brochures explicitly said “toddlers and pre-schoolers” and my

audience were Latinos. My second storyteller job was with elementary school

children and it was done in English. Even when dealing with adults, knowing in

advance that you will be addressing senior citizens, middle-aged housewives, or

teenage boarding school students helps you prepare tales, props and mood.

When your

book hits the market you don’t know who will be buying or reading it. Whether

it comes from New York Times reviewers or by readers complaining on the Amazon

boards, reactions to or interpretations of a novel may shock its author. The

storyteller gets to face the reaction immediately and has a chance to discuss the

interpretation or even change it, because storytelling is always an interactive

activity. So interactive that in some cultures the listeners actually interrupt

the session with questions and even offer suggestions to improve the

storytelling.

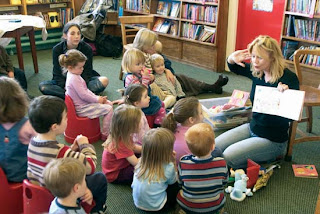

There is tremendous

power in storytelling for narrator and public alike. When my mother saw the snapshots

of my first story hour she was more impressed by the children’s expressions

than by her daughter’s antics. “Look at their little gaping mouths!” she said.

I know what it’s like to captivate an audience as well as I know what it feels to

be enthralled by a fine storytelling session, or by a book that fulfills my

emotional needs or by a television show that grips my attention while bringing

comfort to my exhausted mind.

Modern

authors tend to forget and forsake the pleasure of interacting. They cherish

(sometimes with good reason) the distance that separates them from audience. A

true storyteller would never sacrifice his chance to know the feedback of

listeners/readers and would find a way to recognize and meet their needs.

Can you think of a novelist, or scriptwriter

who combines the quality of fine fiction writing with strong storytelling

skills?

+2.jpg)