“What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist.” ~ Salman Rushdie

|

| Sir Salman Rushdie |

The hero and villain are clear in this story: Rushdie, on the side of democratic values and free expression, is the good guy. The Ayatollah Ruhallah Khomeini, who called for Rushdie’s head? Bad guy. We can all rally behind Rushdie. We champion his right to offend without breaking a sweat … mostly because he doesn’t offend us.

But what about the case of Nakoula Basseley Nakoula?

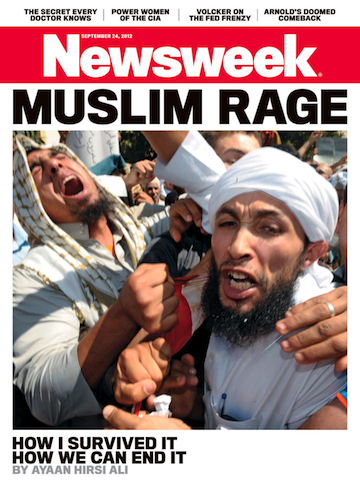

Several weeks ago, a trailer for a low-budget film went viral on YouTube. The film was reportedly made in the US by Nakoula, an Egyptian-born Coptic Christian, and was intended to do what it accomplished: really upset Muslims. Riots and protests have broken out all over the world in response to the clip, often from people who haven’t seen it. As with Rushdie’s novel, the protesters just know that their religion was insulted: they don’t ask for details.

Most of us in the US are appalled by Nakoula and his film. We want nothing to do with him. Thanks, but we’ll stick to defending Rushdie. The problem? This easy-out allows those who are most easily offended, who are least reasonable, to decide what everyone else gets to say. That’s not the point of living in a democracy. We went through that whole Enlightenment thing not just to defend the likes of Rushdie (easy) but to defend the likes of Nakoula (ick). We can, and should, denounce the content of Nakoula’s film: it was, according to virtually all who have seen it, obnoxious and incendiary. But we should also, and more loudly, denounce the protesters who hold an ideological gun to our heads, and tell us we better speak the proper speak or the world will go up in flames. We cannot allow their outrage to control our tongues.

|

| A loud minority |

The United States indeed has no blasphemy laws per se, and fewer hate-speech laws than, say, Europe, where Holocaust denial is illegal. In contrast, many Islamic countries have no free presses at all, only government-controlled media. Blasphemy is criminalized and strictly enforced. It is difficult for people in such places to understand that anyone can say pretty much anything in a democracy: the government doesn’t vet or sponsor the speech of its citizens.

While many in the western world accept the notion of free speech, we can be a little muddier on how it plays out. I am free to tell my Scientologist friend* that her beliefs are ridiculous, that Xenu the Intergalactic Overlord is a sham, a joke, a way to part fools from their money. And by “I am free” I mean my friend cannot have me arrested for hate speech or blasphemy. The government can’t censor me. I am not, however, free from my friend’s reaction to my opinion. My friend can argue with me, delete my posts, unfriend me. When I decide to question her beliefs, I have to deal with these potential consequences. As obvious as this may seem, it’s a concept too many free-speech advocates struggle with: Our freedom to offend doesn’t protect us from anger. This is quite a serious limit on speech, actually: we have to live alongside other people. Just because we can’t be jailed by an action doesn’t mean it’s consequence-free.

As a writer, I frequently self-censor for this reason. I worry that my autobiographical fiction might upset a family member or friend, and I take pains to disguise an anecdote to avoid offense. I worry that a liberal use of foul language or sexuality, appropriate and honest as it may be for the scene or character, will cause an agent, editor, or audience to turn away from me. Writers may also self-censor if their viewpoints on religion, sex, class, and war stand apart from their peers, and this is more insidious. We may feel we must bend to the mainstream in order to have a voice. But if we do that, what are we really saying? In fact, we have nothing to say at all. We’re just parroting the zeitgeist: we end up in an echo chamber. The most influential and important voices are those that can break out of those restrictions and say something new, uncomfortable … and possibly offensive.

This is not to say that offensive speech equals useful speech. Rushdie and Nakoula may both have offended Muslims, but only one had anything constructive to say. Offensive speech can be quotidian or game-changing: the offense in itself isn’t the point. The content is the point. To be a game-changer, you’d better have more than just the ability to piss people off. You had better be able to make them think.

| Gay Talese, Susan Sontag, Norman Mailer, and Gore Vidal |

I think that point is debatable, as we do have the Sam Harrises and Richard Dawkinses of the world—but they are not novelists. I recently reread Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale, which imagines future America as a tyrannical theocracy, and Steinbeck’s grim call for reform, The Grapes of Wrath, and I wonder where we can find such impassioned, daring novels today. The subject doesn’t have to be religion: it can be politics or economics. Steinbeck and Ayn Rand each vehemently criticized economic systems, though in completely different ways. A quick glance through the past decade’s literary standouts fails to reveal anything similar. Novelists can have an enormous impact on culture: Conservative politicians today cite Rand as if she were an actual economist, and Orwell’s novels serve as an admonition across the political spectrum. Today, when we want to warn against the dangers of government surveillance, we still have to say “Big Brother is watching you!” We’ve come up with nothing better on that front since 1949.

|

| Not banned from MY bookshelf |

At its peak, Phillip Pullman’s series His Dark Materials was ranked second in the top-ten books people have tried to ban in the US. The series has a question-dogma message buried within its exciting adventure plot—buried, but not deeply enough. The easily-offended caught wind of blasphemy and pounced right on the series, denouncing it and demanding it be removed from libraries.

In response, Pullman told the Guardian newspaper, “Of course it's a worry when anybody takes it upon themselves to dictate what people should or should not read. The power of organized religion is very strong in the US, and getting stronger because of the internet.” Possibly the most famous challenged author of recent years is, of course, JK Rowling, for her Harry Potter series. Before he was made Pope, Joseph Ratzinger himself condemned the books, writing that their “subtle seductions, which act unnoticed ... deeply distort Christianity in the soul before it can grow properly.” One cannot imagine Ratzinger read the series any more than the Ayatollah read Rushdie. At least nobody asked for Rowling’s head.

| Burning blasphemous books at a church in Shreveport, LA |

At last week’s UN General Assembly, many Muslim leaders called on the international community to tighten restrictions on free speech and to ban blasphemy. Egypt’s new president said that his country “respects freedom of expression” unless it is “used to incite hatred against anyone [or is] directed toward one specific religion or cult." In other words, free speech is great as long as it’s totally inoffensive. The president of Yemen opened his speech to the UN by demanding similar limits to free speech: “These behaviors find people who defend them under the justification of the freedom of expression,” he said. “These people overlook the fact that there should be limits for the freedom of expression, especially if such freedom blasphemes the beliefs of nations and defames their figures.” The Arab League’s secretary-general went further still, proposing a binding “international legal framework” to “criminalize psychological and spiritual harm” caused by statements that “insult the beliefs, culture and civilization of others."

Criminalizing “spiritual harm?” One can only imagine what George Orwell, Ayn Rand, and Margaret Atwood would have had to say to that. It is up to us, as writers, not to allow the outraged to silence us. If we aren’t actively writing “blasphemous” books, we ought to be doing everything we can to stand up for those who do.

*My “Scientologist friend” is purely rhetorical: i.e., nonexistent.

|

| OK! I'm done! I'm done! |

Very thorough and very well written, Sister Steph. I remember watching a news broadcast one day following the brouhaha in a Mideastern country. The reporter (very brave soul, if you ask me) asked an obviously Muslim woman (because of the way she dressed) if she believed in freedom of speech. "Of course," she said. "But not when it comes to our religion." I think that pretty much sums up all those protesters' thoughts on that crappy little movie on YouTube.

ReplyDeleteAs an American, I believe we have the right to say whatever we want. But yes, you're right, what we might say can make another person angry and those are the consequences we have to deal with. When it comes to literature, we have to decide what we see as good for ourselves. We can read whatever we like, but we all have different tastes and belief systems. Although I read so many different types of literature, there are ones I stay away from because of personal beliefs, or simply because I'm not interested in the genre. But that's not someone shoving it down my throat, it's just me deciding what I see as good, bad, boring, or just plain beyond what would interest me.

Precisely! I heard a great quote from Anna Quindlen about offensive language and free speech: "Ignorant free speech often works against the speaker. That is one of several reasons why it must be given free rein instead of suppressed." Usually people like Nakoula will bury themselves with their stupid opinions: we don't need to do it for them.

DeleteVery current, but very thorny subject.

ReplyDeleteI read The Satanic Verses, in its day, when it was subject of controversy, and found it rather dull. However, as a religious person I resent the mocking of any religion. And yet, a “fatwa” was extremely “extreme.” Wasn’t it enough to boycott/burn the book like The Bible Belt did/does with Harry Potter?

Moving to the present uproar. I can understand moderate Muslims feeling confused and hurt because the USA does little to punish the culprits. Perhaps USA should have anti-blasphemy laws, but do they help? Denmark has an anti-blasphemy law that has not been enforced since the 30’s, despite the recent proliferation of anti-Islam cartoons. Bangladesh makes it a criminal offense to display disrespect against ANY religion, but that has not stopped the present anti-Buddhist persecution.

Most European countries are repelling those anti-blasphemy laws because they do more harm than good. Imagine if there were laws in America that made irreverence against other religions (Christianity included) a crime? They would make life inconvenient for many people. Even using (in common speech) the L-rd’s name in vain could be punishable.

And about why novelists have little impact in culture the answer is simple. People do not read, if you have something to say or to protest about, is much more practical to go out in the street hurling stones against something or someone, or making a video and hanging it in YouTube.

"Imagine if there were laws in America that made irreverence against other religions (Christianity included) a crime? They would make life inconvenient for many people." It would be far more than inconvenient: it would be a travesty. We live in a democracy. Free speech is an essential cornerstone of democracy: to give that up would be to give up on democracy itself.

Delete"Perhaps USA should have anti-blasphemy laws..." Do you really think so?

Sister Steph,

ReplyDeleteYou've made an excellent point: in order to make a change, you must make people think, not offend them. After all, defensiveness and anger are never conducive to dialogue. Unfortunately, not everyone aims to have a healthy debate. One of the actresses in the infamous film you mention said she didn't have any idea that it was going to be about Mohammed. Apparently, the director told them it was about some random Muslim guy called “George” (I don’t know if she’s lying to protect herself, if she’s too innocent or if she chose to believe him in order to be in a film, but it seems hard to believe that she (and the rest of the crew) would have bought this.) However, if you look at the film, you can see that some portions were, in fact, dubbed. So the filmmaker KNEW the kinds of consequences his film would have (based on recent history) and it seems likely that his intention was not to have an open dialogue about Mohammed, but to shock, offend and cause an uproar (which he did). In my opinion, this “free speakers” are not achieving anything positive. Just endangering the lives of Americans abroad. I understand the indignation of the Muslims protesters, but what I don’t understand is their reaction. Why are they protesting against Americans when the filmmaker was EGYPTIAN??? It’s like punishing the neighbor for something another kid in the block did just because he’s closer. It doesn't make any sense.

On the other hand, I don’t think “Blasphemy Laws” are the solution because, where do you draw the line? It’s OK to insult Jesus/Christians because they’re more “laid back” and don’t react violently? I understand that it’s not all Muslims who react with violence, but one common behavior I have noticed from moderate Muslims is to justify the bad behavior of the protesters (“Well, if you look at American foreign policy then bla, bla, bla”) instead of condoning their wrongdoings and getting angry at them for making them look bad.

"One of the actresses in the infamous film you mention said she didn't have any idea that it was going to be about Mohammed." I heard that too, and that she was paid $500 and needed the money. The quip I heard in response was, "Hasn't this woman ever heard of porn?" Ha. It does seem remarkably clueless of her not pick up on something a bit suspicious about that whole setup. I am certain you are correct that the filmmaker only intended to insult, not to debate or discuss ... Rushdie, on the contrary, was flabbergasted that his novel provoked outrage, as there's very little (I hear, I haven't read it yet) provocative about it. That Nakoula and Rushdie could both end up with a $500,000 bounty on their heads, issued by essentially the same group of people, is bizarre. Clearly, the intent of the "artist," the content of the "art," and the reaction of the radicals have almost no relationship to each other. As Rushdie said, "There's an outrage industry, people who look for things to provoke their audience. It is, to large extent, manufactured." Political leaders with a clear agenda wait for the right moment, point to something theoretically offensive, and say "Go." Boom: instant riot.

Delete"Political leaders with a clear agenda wait for the right moment, point to something theoretically offensive, and say 'Go.'"

DeleteI think you're absolutely right. That is why I have always hated politics. I believe most people are in it for their own selfish interests, be it power, money or to push their agendas on others. Perhaps my disenchantment is a result of where I come from, where you have presidents who after four years of office become millionaires, move to mansions overseas and never work again. Meanwhile the public hospitals are so poor people have to lie down on counters/desks/chairs and their family members are given a list of items to get their patients (band aids, pain killers, syringes, etc). The corruption there is unbelievable.

Stephanie,

ReplyDeleteGreat, relevant and thought provoking article!

Mary Mary, Malena and Lorena all make thoughtful comments too.

I can say that living here in the Middle East it is frustrating when this stuff happens because the people here will never truly understand Freedom of Expression in a Western context, particularly the American brand. I have had many a discussion about this with my Arab friends and acquaintances and even the most pro-American and freedom loving were still deeply offended by this movie and mystified by our Government's lack of action to censor it.

I have to say that I found the movie to be offensive and from a practical point of view it made my job here much more difficult than it needs to be.

However, hurt feelings in the Middle East, America or anywhere else in the world can never be allowed to change our way of life!

Major H

You are probably the only person I know who has actually seen the movie, Major H! I hear it was as offensive in terms of production and acting as it was in content. Do the locals you speak with understand that it was made by a fellow Egyptian? My guess is there's quite a lot of chatter about it that's demagoguery and not fact-based. And I hear rumors that it was exploited by AQ to as a propaganda tool. I suppose we'll hear more about this in the next few weeks.

DeleteThanks for chiming in. :)

I could only stomach about 6 or 7 minutes of the "film". Think school production or B-rated movie where actors are superimposed over a scenery. Add bad acting, bad quality and uncomfortable situations to watch. I was offended and I'm not even a Muslim! But I think they are giving it too much importance. It's not like it's a Hollywood production being distributed all over the world. It's a lame You Tube clip.

Delete"Six hundred years ago we would have been burned for this. Now, what I'm suggesting is that we've advanced."

ReplyDelete-John Cleese defending the film Life of Brian on BBC chat show Friday Night Saturday Morning (9 November 1979)

Spot on! Now, are you with the People's Front of Judea, or the Judean People's Front?

Delete:)

DeleteThis morning a story popped up in my news feed I want to share: "Muslims for Free Speech," by William Saletan for Slate Magazine. I hope our readers here take a moment to read it.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/frame_game/2012/10/muslims_for_free_speech_can_islam_tolerate_innocence_of_muslims_.html

Some highlights:

'The riots and the lectures paint a picture of Islam as a culture allergic to unfettered free speech. That picture is misleading. There are Muslim liberals. They don’t show up on your TV screen, because they don’t riot. Today, they’re a small minority of the Muslim population. But with the help of global communications technology and the Arab spring, they’re beginning to make a case for greater tolerance. Here’s a sample of what they’ve said about the latest affronts to Islam: the video, the “savage” subway ads in New York, and the Mohammed cartoons in France. Their words and thoughts are worth your time.'

"Governments and individuals frequently abuse national blasphemy laws to stifle dissent and debate, harass rivals, legitimize mob violence, and settle petty disputes. The loose and unclear language of these laws empowers majorities against dissenters and the state against individuals. They provide a context in which governments can restrict freedom of expression, thought, and religion, and this can result in devastating consequences for those holding religious views that differ from the majority religion, as well as for adherents to minority faiths. … Rather than criminalizing speech, U.N. member states should step up their commitments to fighting hate crimes, countering hateful discourse, opposing discrimination and promoting interfaith and intercultural dialogue. “ —Muslim Public Affairs Council and Human Rights First

“The truth is that as amateurish as the movie production is, it still falls in the category of freedom of speech. If you say that to people here, they will read your response as: ‘You accept this. You are a blasphemer.’ They still don’t understand that they don’t have to accept it. They can oppose it, but in a civil manner that is more constructive.” —Ebtehal Al-Khateeb, professor, Kuwait University

“Yes the film was bad, yes the film was intolerant, and yes it poorly reflects the values that most Americans uphold, honor, and believe in. … How about growing some thick skin, brains, and actual faith next time and not necessarily in that order. Make a rebuttal film, challenge to a debate, hold a press conference,… do SOMETHING that shows that Muslims are not a bunch of horned up teenage males with mommy-daddy issues and a lack of viable outlets.” —Robert Salaam, The American Muslim

“I would ask Muslims to recognize that the best way to oppose hate speech is to ignore it. Reaction is precisely what a hater wants to provoke. We can show the falsity of their messages simply by turning our backs.” —Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, founder, Cordoba Initiative, and former lead advocate of the (not) Ground Zero (not) mosque

How refreshing. Thanks for sharing.

DeleteWhat gets me is that they go and burn and destroy their own backyards while chanting "Down with America!" It makes no sense. Why destroy yourselves over something so minute?

ReplyDeleteGreat quotes, by the way!

Stephanie,

ReplyDeleteYou are right about the poor quality of the film. And yes where I am the truth came out in the media that it was produced by an Egyptian Coptic and that it was not truly a full length film shown in the theaters as was originally portrayed by the media. But it took about five days before the real truth came out.

Yes, I believe that virtually every active Salifist group (not just AQ) utilized this film for propaganda purposes and that has contributed to the violence and general instability of the region.

Major H

Thanks again for your insight, Major H. I appreciate the perspective we don't get to hear much otherwise.

Delete