Eight Places to Find Inspiration When Your Mind Goes Blank

|

| The Inspiration of Saint Matthew (1602) by Caravaggio |

Here are the eight places where I’ve found inspiration when confronted with this dilemma (and some of them are currently helping with my third novel):

1. Family stories

I have yet to meet a family where there are no secrets or conflict. I wrote an entire novel inspired by my mom’s stories growing up in South America in the fifties/early sixties. The perfect setting for my novel came from my dad’s hometown and the music and traditions he loved. Like Stephanie said recently in her Bradbury Chronicles post, writers are natural observers and have an innate curiosity in others people’s lives (please don’t call me a gossiper! I’m just doing research!) I think this curiosity translates to others because, very often, people confide in me their problems with their families and spouses. I happily lend an ear and store this information for future use in my fiction.

2. Talk shows

I know. You’re smirking and rolling your eyes as you read this. But don’t be so quick to brand all TV shows as trash. That apparently trivial and sensationalistic venue sometimes offers hidden jewels for writers. Just recently, the solution for a writing dilemma came to me through my favorite Spanish talk show Quien Tiene la Razon (Who is Right?), a show hosted by Dr. Nancy Alvarez, a charming Dominican psychologist and sexologist who helps people fix their marriages and family feuds with well thought-out advice and humor.

3. Cop stories

Being married to a cop, I have a fresh supply of dramatic stories and conflict. I also have a free advisor when it comes to realistic action scenes, police procedures and trials. My advice? Befriend a cop or detective and invite him for dinner and drinks!

4. Dreams

We are fascinated by our dreams. Surely everyone has been intrigued by a dream at some point and even wished it were real. The opposite is true, too. Sometimes waking up from a nightmare is a relief. I don’t know about the rest of you, but many times I’ve dreamt of strangers in intriguing situations (or myself in an alternative life) and I’m frustrated when I wake up. I want to know what happens next! Sometimes it’s just a scene or an image. Other times it’s a sequence of scenes. Ever experienced this? Well, I recommend you write them down as quickly as possible (dreams are more elusive than muses and fade away pretty quickly!) Don’t be surprised, though, if when reading these ideas years later, you don’t remember what was so compelling about that dream in the first place. However, you never know when a seed may germinate.

5. Other works of fiction

Your favorite works of literature can inspire you. (“I’d love to write a story like that!”) The fiction that you despise can also help you. (“That book sucked. If it was up to me, I would change this and that.”) The more you think about ways to fix a book, the more it becomes independent from its original source and before you know it, voila! You’ve created a new story. Song lyrics (especially the ones that tell a story) can also be stimulating. When uninspired, look for books and films of genres you enjoy for inspiration. How would you make that story better?

6. Earlier ideas

Recycling is not limited to plastic and paper. All the darlings you’ve killed on previous novels, all the images and bits of information (ok, you can call it gossip) you’ve collected throughout the years can come in handy when you need an idea. Perhaps you had a great concept years ago, but you hadn’t developed the skills to execute it properly. Maybe the time has come to tell that story and it’s just waiting for you to find it.

7. History

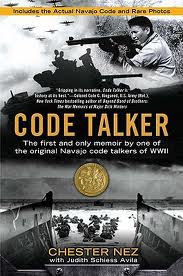

History is filled with extraordinary people and dramatic events. If you’re fond of historical fiction, I recommend you to pick a favorite setting and/or time in history and read about it as much as you can. You may be able to find an obscure yet fascinating fact that may get your idea started. This is exactly how I found inspiration for my second novel. I knew I wanted to set it on the Galapagos Islands (I’m from Ecuador and have always been fascinated with the mysteries surrounding the islands). I read as much as I could about the place until I came across a little-known historical fact (or fabrication?) From that tiny bit of information (one paragraph to be precise), an entire plot was born.

8. Fantasies

Do you ever wonder what would have happened if you had studied at a different university, accepted another job or never broken up with your high school sweetheart? What if you had gathered the courage to study abroad? Or what if, like Stephanie proposed in her post, a rash action or failure in your past had produced terrible consequences? Fantasies don’t necessary mean that you must be unhappy with your current life. They can just be mental exercises to get you started, so don’t feel guilty or bad about exploring the “what ifs” in your own life.

What do you do when you run out of steam? Can you share your favorite sources of inspiration?