I have

finally understood the flaws in my first and forsaken novel. I wrote it in the wrong

language, I targeted the wrong public (add wrong agents to that) and I selected

themes and settings, that despite their glamour, were not easy to appreciate or

relate to. In our urgency to be original, we may force our audience to waddle through

the peculiar, the unfamiliar and the bizarre, and that applies to foreign

cultures, as well as exotic settings and customs.

Identification

is crucial to establish a connection between reader and story. Any plot or

character quirk that shocks, alienates or angers the reader gives excuse to

throw the volume into the garbage can. Therefore, no matter how exotic the

milieu is, a familiar element must always be present. This not only applies to American readers,

it´s a universal phenomenon. To enjoy a

good reading we need to feel comfortable with the material. Without friendly

crutches, we cannot wander too deep into unrecognizable territory.

Unlike films,

books lack visual props that turn the exotic into the” known.” This is why epic

fantasy writers go through pains to explain to their audience every little

detail of the alien civilization they have fabricated, sometimes even adding

maps to establish a geographical location. I am no friend of “high fantasy.”

The reason I made an exception with Song

of Ice and Fire was George R.R. Martin´s genius in basing his mythical

lands and cultures in historical or earthly references. Thus The War of Five Kings

is inspired by The War of the Roses, the North resembles Iceland or other Scandinavian

lands, and Winterfell is based on old Celtic kingdoms. As I read the series, I visualize the Night

Watch as the French Foreign Legion or The Templar Knights, The Dothrakis as

Huns or Mongols, and Robb Stark as Bonnie Prince Charlie.

|

| "Bonnie Prince" Robb |

Novels, even

historical fiction, may include factors that could prove too outlandish for the

reader to swallow. Historical romances are sometimes discarded if considered

racist or presenting other offensive ideologies. We know child brides, sibling

marriages and good Christians owning slaves are disturbing topics even if set

in days of old.

Foreign

cultures, including those that are part of the Western civilization, have to be

treated wisely. For centuries, the British looked with distrust upon the

French, branding them as a hedonistic and depraved people. A Victorian

habit (later picked up by Americans) was to use French terms to euphemize anything

dealing with sex or intimacy. Ladies spoke of their hygienic habits as doing

“their toilettes”, miscarriages were

known as faux accouchements, condoms

became “French letters” and a deep kiss was described as “a French kiss.” The

French became “The Other” as dangerous and bizarre as the Sioux or Zulu.

To make the

English-speaking world familiar with European decadence and immorality, writers

used the “innocents abroad” subterfuge. Many Americans who couldn´t afford a

trip to Europe got to know all its glitter and wickedness through the works

of Henry James, Edith Wharton, Scott Fitzgerald and Hemingway . Although their

prose was guided by different styles, purposes and ideologies, the aforementioned

writers shared a common bond: their protagonists were Americans that, despite

their wealth or background, had much more in common with the reader than the

European characters they mingled with. Just think of

the bunch of expatriates in The Sun also Rises.

Take a look

at recent New York Times Bestseller lists and you´ll see the formula alive and

kicking. Paula McLain’s The Paris Wife

describes the trials of poor all-American Hadley Richardson struggling with husband

Ernest Hemingway’s philandering in Jazz Age Paris. In The

Expats, Chris Pavone depicts the efforts of an American wife to go native

in Luxembourg after her husband moves the family to Europe. I am not surprised

that these two novels are among the most read in modern day America. What would

surprise me would be a bestseller about the trials of a Luxembourg wife in her

native land.

The

principle of pitting the Anglo protagonist against bizarre cultures has been

widely used in stories set in the Third World which was culturally-speaking

much more alien than Europe, therefore, more treacherous. When writing about

their vast colonial empire, The British made sure to have at least one Caucasian (ergo English)

protagonist usually involved in a doomed relationship with a member of the

foreign culture. You see the formula in E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, in John

Masters’ The Bhowani Junction, and in

Paul Scott’s The Raj Quartet.

This way of

describing the exotic became such a cliché pattern that when Louis Bromfield

wrote The Rains Came he had as

protagonist an expatriate half-American, half- English nobleman who divides his

affections between the teenage daughter of a Southern missionary and a British

aristocrat. The latter, Lady Edwina Esketh (faithful to the other cliché) dooms herself

by falling in love with an Indian doctor. Even Ruth Prawer Jawhalah, an

Austrian Jewish refugee married to a Hindu, relied on the familiar formula in Heat and Dust, the story of two British

women that, on different generations, travel to India and get pregnant by

Indian men.

Many English

authors have made careers abusing the “innocent abroad” formula, from John Le

Carre´s British spies gallivanting over Eastern Europe to Graham Green’s proper

English gentlemen meeting danger in some Latin American spot. This applies to

Australian authors as well. James Clavell uses it to expose Japanese

Sixteenth-Century culture in Shogun

and Nineteenth-Century China in Tai-Pan.

To interpret the Indonesian Revolution, Christopher Koch does it through the

viewpoint of an Australian journalist in The

Year of Living Dangerously.

Despite how

sympathetic the authors were to foreign culture, or how much they loved the landscape,

they always reverted to the safe recourse of exposing it through Caucasian eyes.

This was not racism, but the need to describe the bizarre through familiar eyes.

It´s why bestsellers like The Godfather

and The Joy Star Club can safely

foray into alien cultures because the main plot deals with Italo-Ameticans and Chinese-Americans

living in United States. It reminds me of the first agent I approached. I

picked him because his advertisement said he was desperately seeking novels

dealing with Italian characters. I sent him my manuscript, the story of an

Italian girl growing up in Fascist Italy. He rejected it politely saying he was

looking for something “about Italo-Americans.”

The Godfather-Sicilian sojourn

There are

some exceptions to the rule, but beware! Under scrutiny we find that same

prototype underneath “exotic” bestsellers such as The Kite Runner, and Lisa See’s novels about old China. Both Khaled

Hosseini and See are American-born, they write in English, and are familiar

with the culture, way of thinking and language of their target audience. They have

ways to make the exotic familiar and avoid the hazards of the bizarre.

The exotic

does not only refer to other cultures, it could even be a genre. Traditionally,

military fiction and spy novels target a masculine audience. According to

statistics, in United States more women read and buy books than men. How to make

“masculine” subjects attractive to them? Well, it´s a little like making children

eat their spinach. The plot has to disguise the bizarre aspects of the offensive

subject and present it in ways The Readerhood finds familiar and appetizing

such as having a female protagonist.

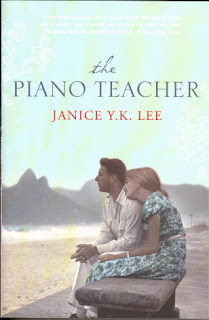

When doing

research for my previous entry on military fiction, I went through American

bestsellers of the past five years. I found that the few that actually dealt

with war had women as protagonists (War

Brides, The Piano Teacher and

currently The House at Tyneford). In these

stories, the battlefield becomes a peripheral subject. What matters in War Brides is the clash between British

women and the culture they spouse after marrying American soldiers. In The Piano Teacher, an English woman in

Hong Kong is involved with an enigmatic countryman marked by his World War II

experiences and in Tyneford, a Jewish

girl, fleeing the Nazis, finds shelter as a servant at an aristocratic British

manor.

How

different from another war novel that briefly passed by the NYT list. I am

talking about David Benioff’s City of Thieves

(2008). Benioff is a very famous screenwriter,

telling you that his credits include “Troy,” “The X Men,” “The Kite Runner” and

“Game of Thrones” (which he also produces) tells you all. Aside from his

brilliant scriptwriting career, Benioff has also written and screen-adapted The 25th hour, another

bestseller and a bit of a cult book. With those impeccable credentials, he adventured

himself into historical fiction with City of Thieves.

|

| David Benioff |

Set in

besieged Leningrad during the Second World War, the novel follows the adventures

of a teenage boy and a much older deserter throughout the city´s underworld and

further into partisan land and eventually the German lines. Full of tragedy and

black humor, this combination of coming-of-age novel and war- buddy drama

reminds me of the great masterpieces of the picaresque novel with this blend of

humor and horror. The naïve hero and his rogue companion become a sort of Russian

Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer.

I love City of Thieves but I sincerely doubt

the book would have made it to the bestselling lists if Benioff had not

authored it. The subject matter and setting are too foreign to appeal to the

average reader. While praising the novel, reviewers concur that Americans know little

(and care less) about the Eastern Front or Russian experiences during WWII. A

telling sign is that despite Benioff’s clout in Hollywood, the novel has not

merited a film version.

As I said

at the beginning, this form of ethnocentrism is not an American trend only.

Just as Hollywood needs to remake foreign films, in Latin America, successful

telenovelas will merit different versions from country to country. “Ugly Betty”

was originally created in Colombia for a

Colombian audience, but now it has versions from Mexico to Israel, from Russia

to India.

|

| Yo soy Betty La Fea (The original) |

|

| Ugly Betty (the remake) |

The

principle behind this remake fever is the same one that has Hollywood creating a

local version of “The Girl with The Dragon Tattoo.” Some members of the audience will need to see

a good story reenacted by their own actors, speaking in their own language or

accent, and expressing their cultural idiosyncrasies. That is conductive to

create the relaxed and cozy atmosphere needed to enjoy a film or a book.

Going back

to literature, it is my experience that only two genres bypass the formula and

safely waddle into exotic cultures: mysteries (historical and others) and the

late Twentieth Century bodice-ripper because they turn around universal subjects:

murder and sex.

In your reading

habits, have you noticed this need to blend the exotic with the familiar? Do

you seek stories or characters that you can identify with? Do you reject novels

that deal with subjects that are so alien to the point of making you

uncomfortable? Gives us examples.

"...the need to describe the bizarre through familiar eyes."

ReplyDeleteThis also applies to fantasy. We see it in "Chronicles of Narnia" where the children are normal human beings who, together with the audience, discover a fantastic world.

I can think of other examples where I've seen this "identification method": the film "The Last Samurai", where Tom Cruise plays an American officer who travels to Japan to train soldiers in modern warfare and is imprisoned by the samurai; the historical novel "Olivia and Jai" where an English woman visits her aunt and uncle in India during the 1840s and falls in love with a "native"; and the musical "The King and I" with Deborah Kerr.

"Some members of the audience will need to see a good story reenacted by their own actors, speaking in their own language or accent, and expressing their cultural idiosyncrasies."

This is so true. I know that in Italy and Spain, for example, movies are dubbed into Italian or Spanish (in Latin America they only add subtitles). The most shocking thing I have seen done in a US Spanish station was that they dubbed a movie from Spain to a "neutral" or Mexican-accented Spanish.

Interesting and thought-provoking post, Sister Violante!

True, I know many people who resent Fantasy unless there are humans involved. I confess that I cringe when I read science fiction or fantasy that is too “bizarre” (e.g. to removed from human sensibilities and realm)

ReplyDeleteThe King and I is actually based on a true story. Anna the governess did exist and she wrote her memoirs about her experiences with the King of Siam in two books The English Governess at the Siamese Court and Romance of the Harem.

For centuries, most probably since Ancient Greeks, foreign civilizations and native customs were exposed through the eyes of explorers, conquistadors and finally diplomats and colonial civil servants. So the formula is derived from the writing style of real life accounts and official reports.

About translations, American audience’s first encounter with Mel Gibson was the Australian flick “Mad Max”. It was so incomprehensible that it had to be translated from “strine” to American English! Poor Mel Gibson got a horrible dubbing! I am sad to say I have never seen the original, so I cannot tell if the language was that indecipherable.

Like you, Violante, I'm not a fan of sword-and-sorcery fantasy, but George R. R. Martin has been an exception. What makes the Song of Fire And Ice familiar-enough territory for me is the political machinations. Politics are politics: the game-playing is easily identifiable almost regardless of culture or even world. Martin only begins to bring in actual magic at the end of the first book, and by the end of the second book (where I am now) there's still not a lot of it: it's pretty realistic. Maybe this is why he's been able to crossover and accrue fans who wouldn't normally read him. Well, the HBO series doesn't hurt. :) There are enough dragons to make the diehard high-fantasy fans happy, but enough actual *story* to make the rest of us happy.

ReplyDeleteI can only assume that you are correct, and that I only read things that are familiar enough to be to be comfortable. I'm not sure how I'd know if there was an exception to that: maybe if I read (for example) Japanese books in translation, written by an author writing purely for his own cohort? I did read "The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle" by Haruki Murakami, which felt pretty accessible to me (though I didn't love it), even though it was in fact written in Japanese originally. But I didn't know Khaled Hosseini had such an American background, or was writing deliberately to entice an American audience: perhaps Murakami also knows western culture and knew to drop enough "western-ness" into his novel to make it accessible to outsiders?

I was really into Orson Scott Card for a while, and loved the Ender series ... until Ender started encountering sentient viruses. The series got progressively weirder, until it was just too oddball for me to follow anymore ... I hadn't thought about it, but this could be another example of your point. Card didn't give us anything familiar to hang on to.

Since childhood I have been a lover of the exotic in fiction, and being a Third World Baby, Americans and their culture were (until my resettlement in USA) exotic territory. I confess that I am still a fairy tale lover, magic and the occult fascinate me, and as a woman of faith I sincerely believe in the supernatural, but I crave for the familiar like anybody else. As you say, Sister Stephanie, when fiction becomes too oddball for my taste, I just walk away from it.

DeleteIt´s why I have never been part of the vampire cult. As they constantly screech to Sookie Stackhouse, having affairs with dead dudes is gross and not very romantic! A werewolf however is human most of the time, so it´s easier for me to relate to having an affair with one. But only when he is human.

Alice Borchardt, Anne Rice’s sister, in her novel The Silver Wolf wrote about a werewolf girl living in Charlemagne days. Excellent novel with one “but.” Regaene, the heroine, falls for enigmatic Maeniel, who luckily for her is also a werewolf. So far so good, but there is a scene where they mate, while in animal shape, that turned me off. I love animals and I have too much respect for them to find their sex habits arousing. I felt like a peeping tom watching dogs copulate.

Oohh, and on the exhilarating and never ending subject of George R.R. Martin´s work. I read yesterday, that his original intention was to write a historical novel about the War of the Roses, but he found more literary freedom when settling his plot in a fantastic realm that kept similarities with our Middle Ages. I agree that keeping magic in its place, and emphasizing more human emotions like the struggle for power, is what has let him gather such a large mainstream following.

I just have to say, I agree with you on having sex with dead dudes -- it's a very repulsive thought. Therefore, I, too, do not enjoy the vampire craze. Here's the most mind-boggling question to some of the vampire stuff -- How does one get pregnant from a guy who's been dead for more than a hundred years? Never mind. I don't think I want to know.

DeleteI never make absolute statements, so I wouldn’t say every reader will feel uncomfortable reading about foreign cultures unless seen through the eyes of someone like him, but most readers do. I don´t think K. Hosseini was attempting to entice Americans to read his novels, no more than we do when targeting a particular audience, but for all effects he is an American. He left Afghanistan when he was five-years old (1970) and didn´t return until 2007. As a diplomat´s son, he had a cosmopolitan upbringing. He settled in the States when he was a teenager, finished high school and went to college in America. He has spent most of his life in California so chances are that his outlook and habits make him closer to the West Coast culture than the Afghani ways.

ReplyDeleteRegis says; I can't think of anything I've read that actually made me uncomfortable, but I have avoided gruesome (holocaust etc) books. If I dip into a genre that bores me (chic lit for example), I move on. Ones that I enjoy, and stay with me, have personalities, not necessarily heroic, with whom I can identify; or are interesting studies of odd characters and interesting relationships. That said, I don't understand the popularity of 'The Sun Also Rises', (Hemingway's worst until The old man and the sea'). The pointless wanderings of a group of drunken misfits, winding up at a bullfight left me cold. I noticed in the clip, (thanks Violante) that the shocking word 'impotent' is used, whereas in the book, it was suggested by innuendo, If I remember correctly . . . . If I had a psychoanalyst, he would probably love to read this.

ReplyDeleteDear Regis, you are so courageous when it comes to postulate your tastes. Most people are terrified of criticizing Hemingway, one of literature’s sacred cows. I am fascinated by Hemingway the man (can’t wait to see Clive Owen portraying him), but I find that many of his works are overrated. The Old Man bores me to death, and For Whom the Bells Toll is nothing short of dull propaganda, but I do like Sun also Rises. I don´t love it as I love A Farewell to Arms, but I am very fond of the story perhaps because I read the book in college under the guidance of a wonderful teacher who really made me love it. My next post will be about those words like “impotent” that you couldn’t include in novels.

Delete"Going back to literature, it is my experience that only two genres bypass the formula and safely waddle into exotic cultures: mysteries (historical and others) and the late Twentieth Century bodice-ripper because they turn around universal subjects: murder and sex. "

ReplyDeleteI found this final thought of yours intriguing. Recently I read a blog post by a British blogger and she mapped out the top five things to look for in a good mystery. One thing she noted was that she couldn't stand to read about the use of guns in a detective novel, the main reason being culture. She felt that in British literature it makes the story unbelievable, since they are not a culture of guns. With American literature it's quite the opposite. If there's a cop in a murder mystery not pulling a gun, then that becomes an unbelievable selling point to the intended audience. So honestly, I think even mysteries depend on who's telling the story, because a British detective and an American detective would view the whole firepower issue differently.

And now that you've mentioned it, it makes me think of how many recent Masterpiece Mysteries I've watched (because they mostly take place in England, except for Wallander) and how rarely one sees firearms used during these shows, which is quite the opposite when it comes to Hollywood films and television shows.

The subject of vampire pregnancies also baffled me. It used to be that they couldn´t breed. It is still so in the Sookie Stackhouse series, but then Twilight came and changed that perception using no logic whatsoever.

ReplyDeleteMy research threw light on how culturally different British and American Literature are. As you say, you don´t find firearms or car chases, add profanity is much moresubdued in comparison to its American counterpart.